Pay Attention To The Man Behind The Curtain

Just over 100 years ago, an inquiry by Britain’s Parliament sent out a party in a horse and carriage to drive eastward across London, a distance of about 40 miles, to assess the state of London’s roads and traffic. Their average speed was 14 miles per hour. A hundred years later, when another party made the exact same journey in a car, they averaged only 12 miles per hour. And that with a huge increase in carbon monoxide and lead pollution. Is this “progress”? I guess maybe there was more horseshit 100 years ago. Or was there?

Nat King Cole cut “Mona Lisa” in March, 1950, at Capitol Records’ studios on Melrose Avenue. 63 years ago. And it was a huge hit, spending 8 weeks at number on the Billboard singles charts, and establishing him as a major-league solo artist. And when I listen to that cut, it’s hard to imagine a better recording. That voice comes glowing out of the speakers with a perfect combination of warmth and detail, larger than life yet very intimate, and a perfect match for the message of the song. And the sound on the orchestra (to say nothing of a very young Nelson Riddle’s incredible arrangement) perfectly frames a sweet sense of loss and longing, warm and lush and spacious even though it’s in mono. It’s hard to imagine a more beautiful recording, to be honest, and only very rarely do I hear anything like that today. And there was none of the electronic finery we have today, just a great singer, a great orchestra and arranger, great musicians, a great studio, and a great engineer who really understood the gig. Probably very few microphones, not even so much as a plate reverb, a couple early compressors used mostly to keep the level OK for a 78 rpm disc, and very simple shelving EQ. 63 years ago last month.

A few months ago, I was perusing a few video demonstrations of some plug-ins for a series I use. And it wasn’t much of a surprise, but by way of showing off the plugs, a Famous Engineer® shows a mix he recently finished using these compressors. And pretty much every track is crushed to death. 10 db, 12 db, little virtual meters pinned and fairly smoking, and by the end the mix just sounds like a garbage grinder to me. Synthetic. Kind of “like a record”, but not very much like music. And I have to say that, as a musician, this had my eyebrows hovering a foot above my head. Here you have these master musicians working on this large-budget project, and your way of working is that the first thing you do is squash all the music out of what they did so you can remake it in your own image? It’s like making Lucky Charms: you take something that’s natural and beautiful and flavorful and good for you and strip out all the nature and beauty and flavor and good-for-you until you have just this colorless paste. And digital colorless paste at that. Then YOU, using your lobotomized, denatured colorless paste, put all your artificial colors, “flavors” and artificial “nutrition” back in. Hooray, it’s “enriched”! It’s “part of this nutritious breakfast”! These records typically sound terrible to me. And the worst part? It’s that little mosquito whining away in the middle of the big tureen of sonic Soylent Green, sounding like Chris Christie is standing on her diaphragm: the lead vocalist. Even great singers are getting this treatment; I’m often shocked by the harsh, thin sound I hear on singers like Christina Aguelera, who has a nice, full-throated voice in real life. I guess these engineers are going for a “sound”, but I can’t help but wish that that sound included respect for the actual voice at hand, and respect that that should be the biggest (not necessarily the loudest) thing in the mix!

The point I’d like to make about all this is that if you’re a musician who’s spent a lifetime working on your sound, I think you would do well to familiarize yourself with what a “man behind the curtain” can do to your sound, for better and for worse. Does it really make sense to work on your mouthpiece and embouchure and reeds, your strings, your touch, your amp, your synthesizer sounds, your bow, a lifetime’s worth of cymbal collection, your pickups, and then just punt all that into a grab-bag right when it actually gets recorded so everyone can listen to it? If you’re lucky, you can just have James Farber record everything you do. But most of us work often with people we don’t know. Often that’s a really pleasant surprise; I’ve worked with dozens of great engineers who’ve taught me a lot. But other times, you can find yourself getting recorded by someone who doesn’t really know what you or your instrument should sound like, to put it charitably; I suggest that you should be able to bring a basic knowledge of how to get that yourself. I’ve mixed a number of tracks, for example, where the saxophone was recorded into the wrong side of the mic. It happens, and if that’s happening, it’s really like somebody’s taking your exquisite meal at Robouchon and pouring ketchup on it before it’s served to you. I think it’s an essential idea to know as much as you can about how to get a sound you like onto the disc, and to know when your sound isn’t right, whether it’s a technical problem or whether it’s a man behind the curtain remaking your lifetime’s worth of work in his own image. Especially now when you can create a nice mix on an iPad, it’s never been easier to familiarize yourself with what all those knobs can and can’t (or shouldn’t!) do. It’s been a very useful thing for me to know what I know about the various different aspects of recording; if nothing else, I know when somebody’s doing something to whatever I’m working on that’s stepping on my intent, or taking it in an un-musical direction, or de-naturing it because “they’ve always done it that way”. And it’s great to be able to say “can you back off the ratio and lengthen the attack on the piano” or whatever instead of just “something sounds funny”, especially since in most recording situations (and live situations as well) there’s no eternity to divine what you might mean by that.

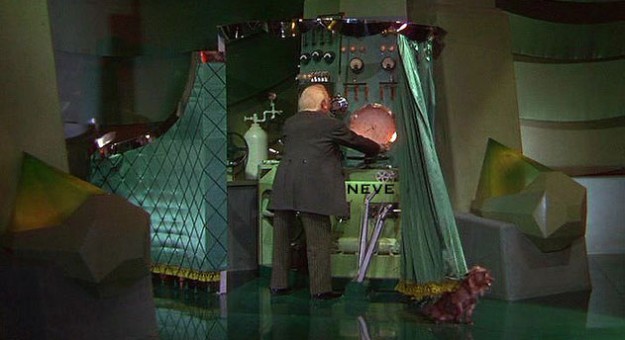

Once upon a time, I was recording at a supposedly famous recording studio in Bridgeport, Connecticut. We were trying to be in and out of there in just a few hours, so we set up, recorded some stuff, and then went in to take a listen. And wow, did my keyboards sound STRANGE. It was hard to tell whether the guy just had very weird monitors, or a bad EQ patched in somewhere on the outputs. but it sounded awful, and I had told him to just record me flat. We kept recording, it kept sounding strange, and finally toward the end of the session I went into the booth, found my inputs and looked at what he was doing with the EQ on the board. It was a Neve 80 series, if I remember right, and he had every band on my EQ turned up all the way. When I asked the engineer, a very over-sensitive type, why on earth he would do that, he responded: “Whaddya mean! All the bands are turned up the same amount, so it’s just adding gain to it!”

Click…click… click….

There’s no place like home!

There’s no place like home!

THERE’S NO PLACE LIKE…

Hear, hear…and I mean that.

You dig! Did you ever run into that engineer in NY whose claim to fame was “I can mix any track in just 45 minutes!”? He used to hang out at Unique. Sort of the Earl Scheib of engineers. And he basically just crushed everything with heavy compression, then spent a half-hour twisting some EQs, and there, you’re mixed in only 45 minutes!

So right. I Hate super squash. I have dismissed artists entirely because albums put out in their name are loud war casualties.

I will be curious to see what they did with the remaster “Still Life (talking)”, one of my all-time favorite CDs. My understanding is that they’re trying to adjust the levels, effectively compressing it so that the very first thing you hear is audible in the car. If I were given that gig, I think I’d ride it by hand rather than try to set a compressor on it. But I hope they don’t screw anything up (I doubt Pat would allow that anyway!), that disc is a real classic just the way they made it…

As a seriously Not Famous Engineer™ I read this when pianist Mark Levine shared it on facebook.

One of my associates and I were talking about just this a few days ago.

it amazed both of us how some of these “men behind the curtain” continued to be employed.

In 40 plus years of live sound and recording engineering work I have never felt it was my job to impose MY idea of what an instrument or voice should “sound like” on the end result.

I have witnessed far to many “engineers” try to do just that. On one occasion while recording an alto saxophonist who’s tone most resembled Johnny Hodges the “man behind the glass” was taking far too long to “get a sound”. I went into the control room to see what the hang up was. As soon as I heard the monitors I knew. He was trying to male the alto sound “like” David Sanborn, his benchmark for a “good” sax sound :-0!

Oy, Johnny to Sanborn, that’s a little tough! That’s what I dig about Farber, everything sounds just like whoever it is, but bigger and more spacious somehow…

G:

Your musings are as worthy of grammies as is your music. The Hancock/Lang Lang piece was magic. Why the F— did someone shelve it????? Seems as if someones sensitivity was compressed to a picogram. Pox upon them.

eD M

ED! There are literally 1,000 moving parts in a project like that, and if a few of them move in the wrong direction the project doesn’t get the green light. We’ll see if anything comes of it down the road; we were going to peel the paint off of everybody’s living room with that disc!